Integrated Roadside Vegetation Management Technical Manual

Integrated Roadside Vegetation Management Technical Manual thompsbbAbout This Manual

The objective of this publication is to provide basic technical support for new and existing Iowa county roadside programs. This manual is also intended to provide guidance to policymakers and engineers interested in adopting or expanding integrated roadside vegetation management in county rights-of-way.

The objective of this publication is to provide basic technical support for new and existing Iowa county roadside programs. This manual is also intended to provide guidance to policymakers and engineers interested in adopting or expanding integrated roadside vegetation management in county rights-of-way.

Producing a manual that accurately describes the various aspects of integrated roadside vegetation management is best accomplished through a collaborative, integrated effort. Many of Iowa’s current roadside practitioners provided valuable assistance to the manual’s editorial team. Their expertise was instrumental to the creation of the manual and is greatly appreciated.

Funding for this manual was provided by the Iowa Department of Transportation's Living Roadway Trust Fund.

The manual was reviewed and updated by a technical review committee (see below) in 2024–2025. Chapters 3, 8, 10, and 11 are newly written for this version. Contact Kristine Nemec with any questions or suggestions regarding the manual: kristine.nemec@uni.edu or 319-273-2813.

Written By

Kristine Nemec

Roadside Program Manager, Iowa Roadside Management

Josh Brandt

Executive Director, Cerro Gordo County Conservation Board

Kirk Henderson

Former Roadside Program Manager, Iowa Roadside Management

Jim Uthe

Deputy Director, Dallas County Conservation Board

Editorial Assistant

Sean Thompson

Graduate Assistant, Tallgrass Prairie Center

Technical Review

Tanner Bouchard

Roadside Vegetation Manager and Weed Commissioner, Dickinson County

Wes Gibbs

Roadside Manager & Weed Commissioner, Jones County

Mike Heller

Lead Environmental Scientist, Foth Infrastructure & Environment, LLC

Chris Henze

Roadside Vegetation Manager and Weed Commissioner, Johnson County

Megan Huck

Vegetation Management Specialist, Linn County

Joe Kooiker

Roadside Biologist and Weed Commissioner, Story County

Kolten Kudart

Roadside Manager, Poweshiek County

Jim Uthe

Deputy Director, Dallas County Conservation Board

Tara Van Waus

Living Roadway Trust Fund Coordinator/State IRVM Program Coordinator, Iowa Department of Transportation

Chapter 1: Introduction

Chapter 1: Introduction thompsbb

What is Integrated Roadside Vegetation Management?

Integrated Roadside Vegetation Management (IRVM) is an approach to right-of-way maintenance that combines an array of management techniques with sound ecological principles to establish and maintain safe, healthy, and functional roadsides. The IRVM toolbox includes judicious use of herbicides, spot mowing, prescribed burning, mechanical tree and brush removal, and prevention and treatment of disturbances such as farm field runoff. IRVM’s long-term objective is to reduce roadside maintenance costs by creating stands of durable, perennial native plants.

History

History thompsbb

IRVM techniques were introduced to Iowa in the mid-1980s to protect groundwater and surface water from herbicide contamination. Roadside weed control had previously relied exclusively on herbicides, with most counties employing blanket spraying (also known as “broadcast spraying”) to spray vast swaths of the roadside.

Besides being expensive and potentially harmful, blanket spraying was unsustainable and ineffective. It created openings for weeds to grow by weakening roadside grasses and eliminating beneficial broadleaf species.

At this time, the Iowa Department of Transportation began using native prairie grasses and wildflowers to control erosion and reduce mowing fuel costs, as native plants require less mowing than cool-season grasses. A few county conservation boards were also experimenting with this naturally adapted alternative roadside vegetation.

In 1988, the Iowa Legislature passed legislation adopting parameters for IRVM into state code (Section 314.22). The program's cornerstone was native vegetation in Iowa roadsides. The Living Roadway Trust Fund (LRTF) was created the following year to support state, city, and county roadside projects. For more information about the history of IRVM and LRTF, see the 2018 report by Jean Eells, “Iowa’s Living Roadway Trust Fund and Integrated Roadside Vegetation Management Program.”

IRVM Program

IRVM Program thompsbbGoals

- Maintain a safe and effective road system.

- Provide responsible and sustainable vegetation management.

- Make the most of Iowa’s immense resource: 847,000 acres of roadside.

Basic Tenets

- Prevent soil erosion.

- Control undesirable species in roadsides.

- Avoid reliance on herbicides.

- Plant vegetation best adapted for the roadside.

The Road to Success for County Roadside Management

- Create a full-time roadside manager position.

- Hire a conservation-minded individual to be the roadside manager.

- Give the roadside manager the power to succeed.

The Integrated Toolbox

- Establish a robust and weed-resistant plant community through species diversity. No single species is adaptable to all roadside conditions. IRVM calls for a mix of species suited to the range of growing conditions found in roadsides and the varying climate conditions of Iowa growing seasons. Planting a roadside with only one species is bound to result in gaps that weeds will exploit.

- Use herbicides sparingly. Overuse of herbicides weakens stands of grass, allowing for increased weed invasion. Careless herbicide use also destroys beneficial broadleaf species that outcompete broadleaf weeds by occupying the same niche.

- Use herbicides effectively by spraying smarter with better training, better timing, and better technology.

- Prevent disturbances from adjacent lands, such as farm field runoff and excessive herbicide use, that destroy roadside vegetation and cause weed growth. Collaborate with landowners to reduce these negative impacts.

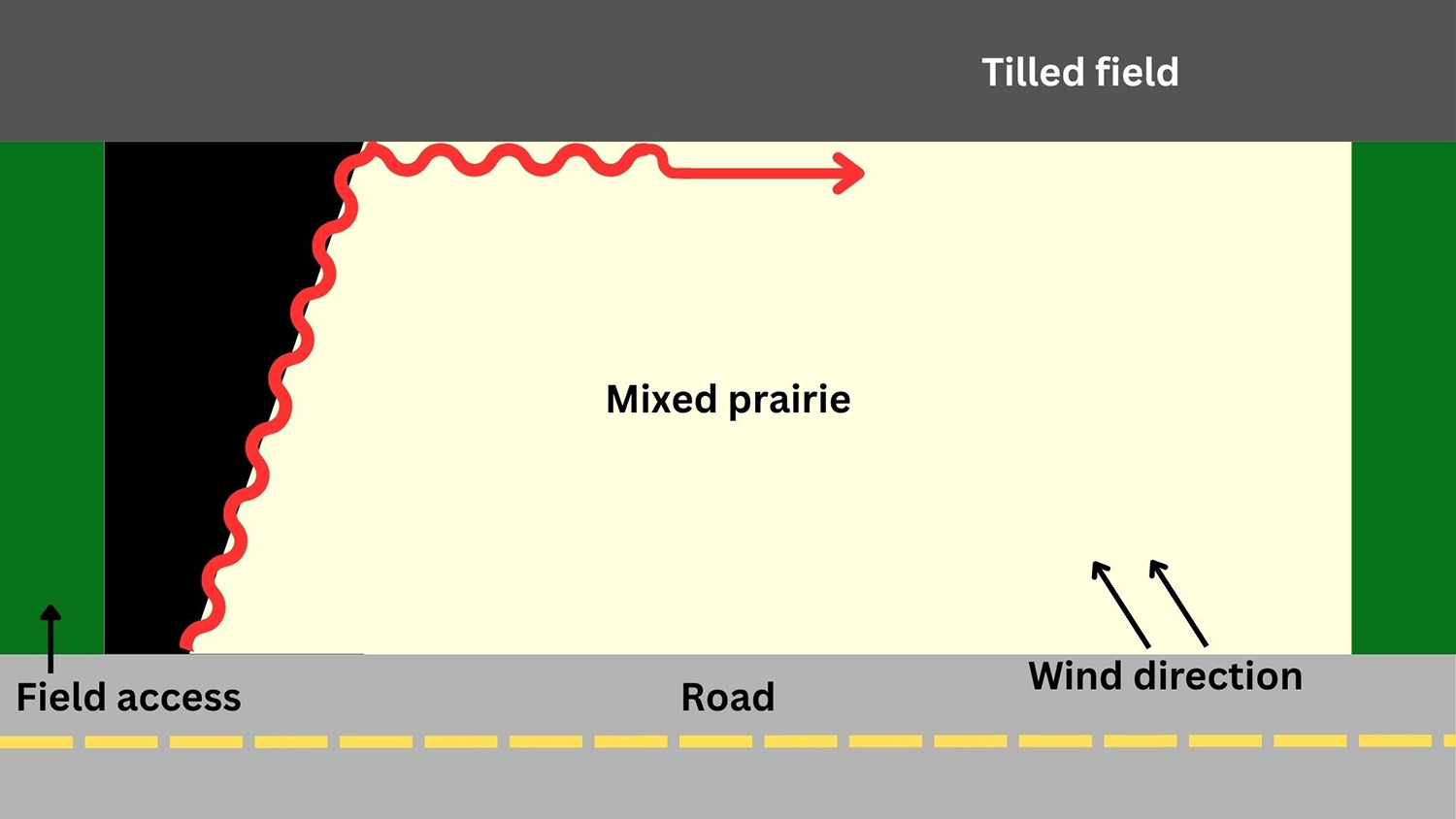

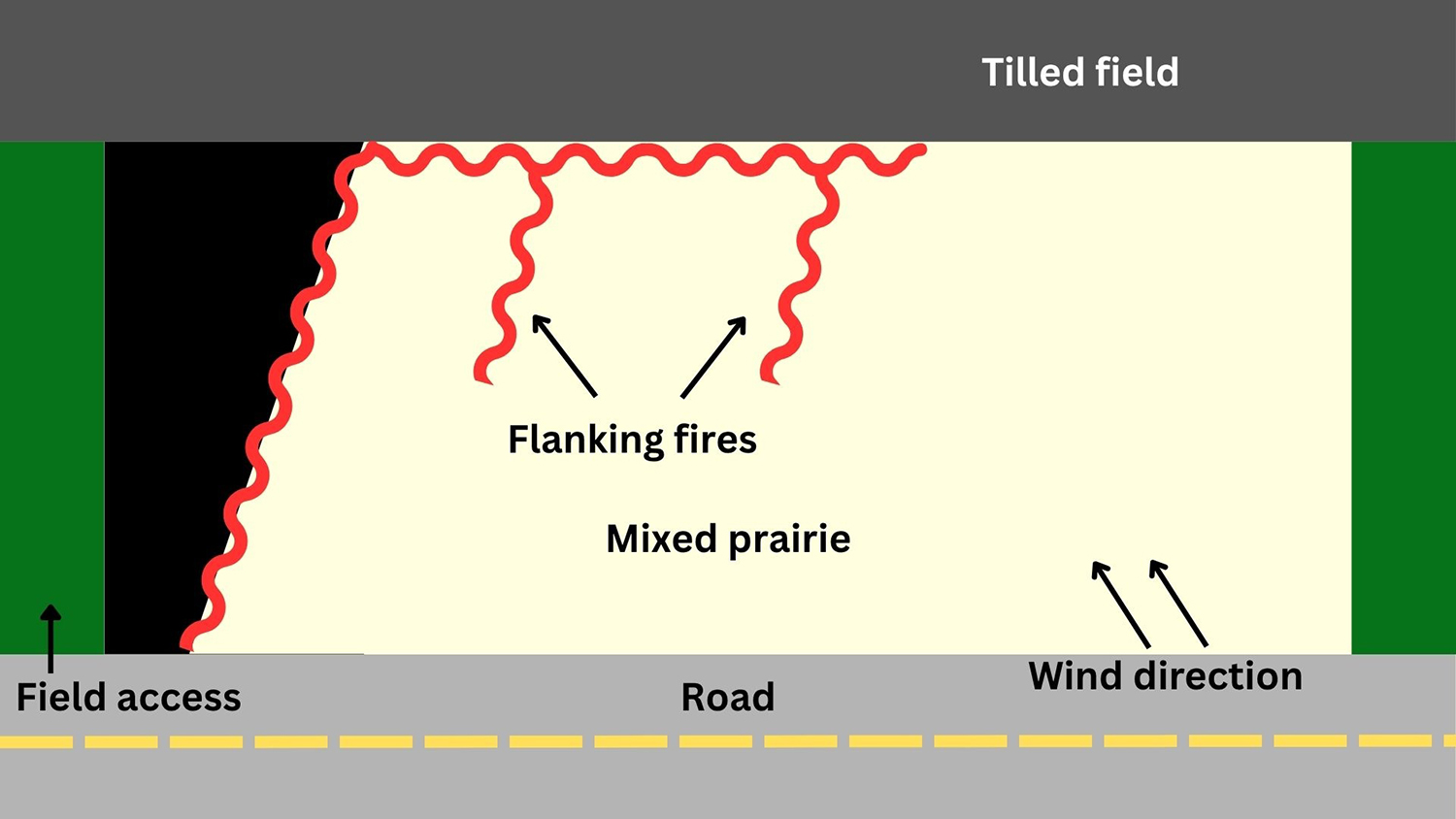

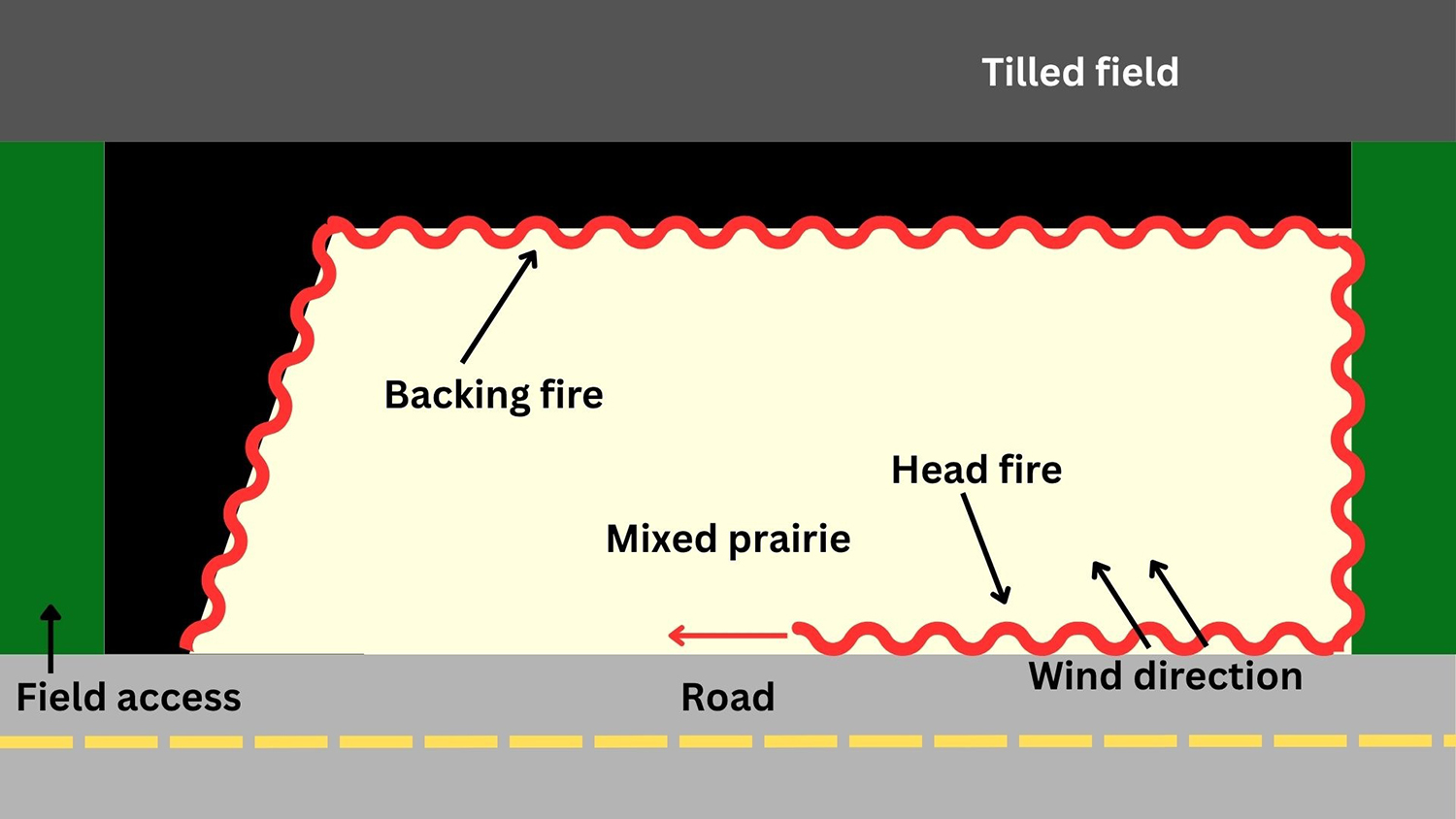

- Conduct prescribed burns to promote healthy native vegetation. Trained and well-equipped crews use fire every 3–5 years as the most effective means of managing fire-adapted prairie species.

- Mow patches of weeds to reduce seed production and dispersal.

- Use various means to clear brush and trees before they block the vision of motorists, obscure signs, and become dangerous obstructions to errant vehicles.

The Benefits of Native Vegetation

- Native plants are durable perennials that are well-adapted to Iowa’s climate and growing season.

- A diverse native planting adapts to a wide range of soil and moisture conditions.

- Native plants perform well in poor soils.

- Native plant root systems are extensive and provide superior erosion control.

- Deep roots and dense aboveground foliage reduce stormwater runoff by intercepting raindrops, slowing water flow, and increasing infiltration.

- Extensive roots and decaying foliage add organic matter to the soil, which makes it spongy and absorbent, resulting in increased stormwater infiltration.

- Root systems penetrate 6–8 feet on average and sometimes deeper, enabling prairie plants to survive drought and high salt concentrations.

- Extensive root systems deprive weed roots of water, nutrients, and space.

- Tall prairie vegetation casts shade on Canada thistle and other weed seedlings, stalling their growth.

- A wide swath of prairie grass in the right-of-way traps snow and prevents it from blowing in some situations, increasing the snow storage capacity of the ditch and reducing the amount of snow on the road.

- Native roadside plantings provide valuable food and cover for songbirds, game birds, and small mammals.

- Native roadside plantings provide essential habitats for agricultural crop pollinators.

- Native plants add color and natural beauty to the right-of-way.

- Native roadside plantings restore a piece of Iowa’s natural heritage—the tallgrass prairie.

Progress to Date

The Iowa Department of Transportation and half of Iowa’s counties routinely plant native vegetation and have reduced herbicide use to spot-spray application.

Since the early 1990s, native vegetation has been planted to over 40,000 acres of state and 35,000 acres of county road right-of-way. Diverse stands of 30–45 prairie grass and wildflower species—all naturally adapted to local growing conditions—provide stable, low-maintenance roadsides for Iowa.

As of mid-2025, 65 counties had an IRVM plan and 47 counties had a roadside vegetation manager. Counties with either a plan or a roadside vegetation manager collectively managed 420,000 acres of roadside vegetation using IRVM principles. There were also 28 cities with an IRVM plan.

The Challenge

Reaching the goal of having a higher percentage of counties and cities prioritize roadside vegetation is challenging, primarily because officials prioritize addressing other issues rather than considering how their roadside vegetation could be managed differently.

According to the 2020 Federal Land Ownership Report, of Iowa’s total land area of 35,860,480 acres (56,273 square miles), 4.3% is public land. Roadside rights-of-way comprise around 60% of this public land within Iowa (see Figure 1.1), representing a significant area where sustainable management techniques can improve water quality, reduce soil erosion, enhance aesthetics, and provide other public benefits.

Chapter 2: Steps to Start a Roadside Vegetation Program

Chapter 2: Steps to Start a Roadside Vegetation Program thompsbb

Before developing a roadside program, it is important to assess the level of community interest and think about how you might structure the program within your county or city. Your program structure and goals can be inspired by conversations with officials and residents from your area, as well as with those who have already implemented successful programs. Once a program is approved, there are resources available for hiring and training staff, acquiring equipment, and implementing a program over the long term. This chapter discusses what to consider at the initial stages of a program.

Evaluate Level of Interest in Starting a Program

Evaluate Level of Interest in Starting a Program thompsbbInitial Considerations

Residents and county or city government employees may be among the first to be interested in starting a program that safely and strategically manages roadside vegetation using the principles of integrated roadside vegetation management.

People are most often interested in developing a roadside program because they want roadside management that is

- organized and proactive;

- responsible and sustainable;

- cost-effective;

- multipurpose; and

- poised to take advantage of the Living Roadway Trust Fund (LRTF) to offset equipment and roadside inventory costs.

Collect Information on the Current Need for the Program

Collecting information will help make a strong case for an integrated roadside vegetation management (IRVM) program to a county board of supervisors or city council that may be skeptical of its necessity. The following suggestions provide a good starting point for considering how much information is necessary to collect for your county or city.

County Vegetation Management Survey

Supporters need to gather the following information demonstrating the need for the IRVM program:

- money and time currently spent on managing roadside vegetation;

- satisfaction levels of county officials and residents with erosion control, roadside appearance, presence of noxious weeds, and safety issues such as the amount of brush near roads; and

- how having an IRVM plan and a roadside manager will provide the resources necessary to proactively and effectively manage the local roadside vegetation.

Obtain data from county herbicide-use records on the amount of herbicide used, the cost, and the products used. Similarly, the county spray records typically provide information about who does the spraying, when it occurs, the technology used to spray, the number of miles covered each year, and the costs.

The County/City Roadside Vegetation Management Survey (Appendix 2A) can serve as a basis for evaluating a county’s roadside vegetation management program. Obtaining meaningful survey data may require interviews with members of the road maintenance crew or others directly involved. Though individual survey responses are subjective, the aggregate data will help identify and prioritize personnel and equipment needs.

Where Are the Savings?

Counties and cities realize long-term savings by establishing native plant species that are better adapted and more competitive than non-native vegetation. Immediate savings are obtained by reducing or eliminating money spent on contractor services by

- using LRTF funds to purchase equipment to manage weeds and brush in-house; and

- installing and maintaining erosion control measures with county personnel.

A professional vegetation specialist on staff can provide additional savings by

- conducting required National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System stormwater inspections;

- doing wetland delineations to comply with local and federal mitigation requirements;

- preparing wetland monitoring reports for mitigation; and

- developing a proactive program of managing roadside vegetation that dovetails with current road maintenance activities instead of a reactive program that fixes problems after they have formed (the savings might be simply doing a much better job with the same amount of dollars).

Potential Objections to Starting a Program

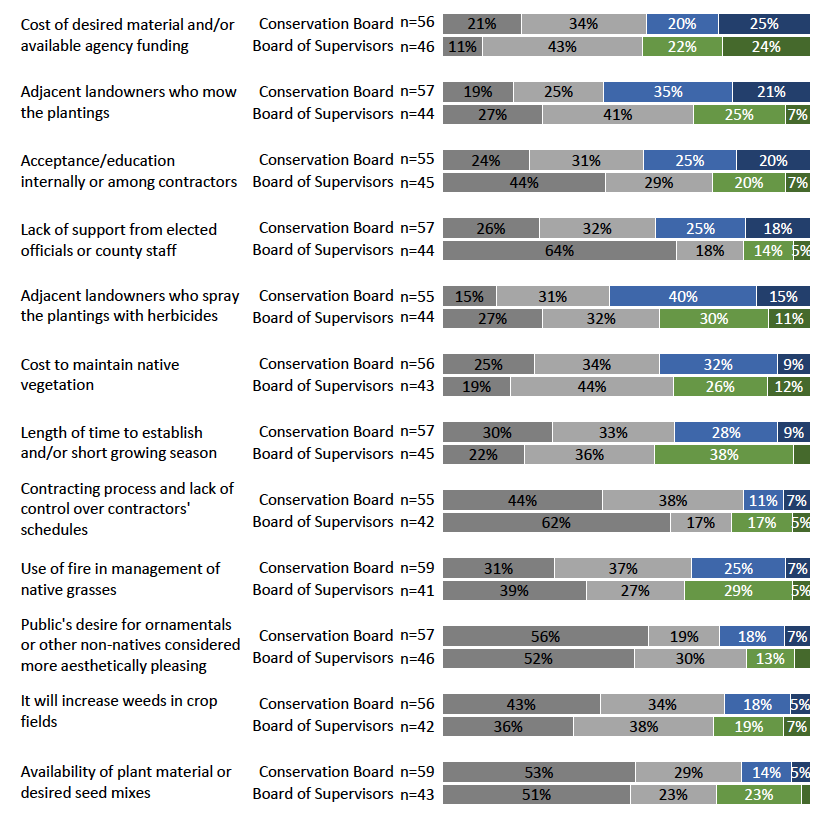

Communicating the benefits of starting a program is important, but it’s also critical to be prepared to address the common objections given by those opposed. According to a 2016 survey of county board of supervisors and conservation board members (Stephenson et al., 2017), the greatest barriers to implementing IRVM practices are

- a lack of support from elected officials or staff;

- a lack of staff capacity;

- other concerns in the county being a higher priority;

- the cost of starting a program; and

- a lack of community support.

Survey respondents said challenges to using native species include cost, adjacent landowners mowing the plantings, and lack of internal or contractor acceptance (Stephenson et al., 2017). A survey of engineers and roadside managers found similar barriers (Stephenson & Losch, 2016). Both reports provide useful background information about how county officials make decisions regarding roadside management. Of course, familiarity with local decision-makers’ values and perceptions of roadsides will allow citizen groups to be prepared for proposing this new initiative.

Proposing a Program to County or City Decision-Makers

Those wanting to start a roadside vegetation program, whether county or city employees or citizens, will need approval from the decision-makers to move forward. This typically means the county board of supervisors, city council, or city administrator/manager who controls the local budget, and the engineer, county conservation board director, board of supervisors, or city administrator/manager who will supervise the roadside manager. Program supporters will typically present the need for a roadside vegetation program at a board of supervisors or city council meeting.

Citizens who want less roadside spraying and more native vegetation often lead the effort to change their county or city’s roadside management practices. This may start with one person or a small group who recruits other citizens to join the cause. Once the group has formed, it can lay out its goals over the course of a few meetings.

The roadside program manager at the Iowa Roadside Management Office is available to answer questions and provide resources to help inform people about roadside programs. For example, the paper “Roadside Weeds, Brush, and Erosion: How Your County or City Can Manage Them to Create Safe, Healthy Roadsides and Roads” details the benefits gained from having a roadside vegetation program. Brochures about roadside programs and roadside vegetation are also available.

When the citizen group is ready, it should ask for time with the county board of supervisors or city council to propose its vision and goals for the roadside vegetation program and request a formal IRVM committee. Unless the board can provide a large block of time during a regularly scheduled meeting, a special meeting specifically to discuss the proposal will allow for better discussion. The majority of the citizen group should be present at the meeting.

Strategically choose the person or people to present about the proposed program based on who local decision-makers would trust the most. In some cases, it should be the county or city employee who would be responsible for developing the program and supervising the roadside manager. In other situations, decision-makers would also want to hear from one or more of the following people: a roadside manager, engineer, or conservation board director from a nearby county with a roadside program; a federal Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) employee; a Soil and Water Conservation District commissioner; the chair of the citizen group; someone representing farming interests; a weed control professional; the statewide LRTF coordinator; or the roadside program manager at the Iowa Roadside Management Office. The goal is to fortify the effort with respected individuals who can address the elected officials with candor and expertise.

No matter who presents, it is crucial to demonstrate local support with a high turnout of residents (ideally including some with political influence) who support the effort.

The desired outcome for this initial meeting is for the board of supervisors to appoint a formal IRVM committee to examine the county’s current roadside management practices and determine what is best for the county. Recommended IRVM committee membership includes one or more county supervisors or city councilors, the county/city engineer, the road superintendent/foreman, the weed commissioner, a member of the county conservation board, and key members of the original citizen group.

Residents can also write letters to the editor of the local newspaper and email or call their local officials to convey their support for the program.

Development of an IRVM Program

Development of an IRVM Program thompsbbThe simplest approach to developing an IRVM program is to think through the following details with your staff, community members, and stakeholders.

Name of the Program

Example roadside program names:

Example roadside program names:

- Shelby County Roadside Management

- Dallas County Integrated Roadside Vegetation Management Program

- Linn County Right of Way Vegetation Management Program

- City of Center Point IRVM Program

Goals and Objectives

Goals are broad, long-term outcomes, while objectives are short-term, measurable actions taken to achieve goals.

Goals

Examples of roadside program goals excerpted from IRVM plans are listed below. Some programs categorize these as short-term goals (e.g., 0–5 years), medium-term goals (e.g., 5–10 years), or long-term goals (e.g., 10–20 years).

- Recognize and stop the spread of newly introduced invasive plant species in roadsides countywide before they become a problem.

- Minimize the use of herbicides and other chemicals to manage or eliminate undesirable plants. This includes the incorporation of prescribed burning, spot-spraying, and strategic use of herbicides, pesticides, mowing, and tree removal.

- Reduce erosion on county road construction projects by seeding and providing adequate erosion control. Use a long-term integrated management program that promotes desirable, self-sustaining plant communities. Whenever practicable, native plant communities are incorporated with roadside vegetation plantings.

- Enhance the scenic qualities of roadsides and their capacity as habitats for wildlife.

- Cultivate a communications strategy to build community support for the roadside management program.

- Develop a neighborly policy for dealing with right-of-way encroachment issues.

- Preserve and manage remnant prairie plant communities in the right-of-way through monitoring, prescribed fire, and brush removal.

Objectives

Here are some examples of specific measurable roadside program objectives from the Dallas County IRVM plan:

- Spray at least 30 gallons of basal bark herbicide annually to control woody invasive plants. Encourage district operators to perform these treatments.

- Monitor mowing operations by secondary road personnel and make recommendations as requested. Encourage prescribed use of mowing to limit impacts on plant and animal resources in the right-of-way and keep the road department in adherence with Iowa Code 314.17.

- Mow all first-year plantings once during the growing season. Mowing will be conducted between late June and early August. Mow plantings established for two years or more only as necessity and manpower dictate.

- Update the website pages related to roadside management annually. Provide two press releases per year about roadside vegetation management to local newspapers. Provide public service announcements and take advantage of other opportunities for exposure.

To get ideas for other goals and objectives that would be appropriate for your county or city, see a sampling of approved IRVM plans on the LRTF website.

IRVM Plan

Counties and cities that want to apply for Living Roadway Trust Fund (LRTF) grants and request free native seed will need to submit to the LRTF an IRVM plan that is signed by the appropriate county or city officials. To formulate the plan, counties and cities will use one of two plan outlines: the IRVM Plan Outline for Counties, State Agencies and Cities over 10,000 in Population form, or the IRVM Plan for Cities Under 10,000 Population form. These forms and approved plans to serve as examples are on the LRTF website.

For most parts of the plan outline, roadside managers and other staff will be able to incorporate information already gathered and created during the new program's planning and implementation. The plan outline may be more or less extensive than the county or city’s internal program documentation. The LRTF coordinator is available for any questions that arise as you work on your plan.

Email the final plan to the LRTF coordinator for approval. Both IRVM plans and LRTF grant applications must be submitted by June 1. Once approved, plans should be updated and submitted for review by the LRTF coordinator every five years.

IRVM plans developed prior to 2015, when the LRTF implemented the latest plan requirements, are considered inactive. Counties or cities who do not have plans that meet the latest requirements are ineligible to apply for LRTF grants or request native seed.

Staffing and the Percentage of Time Each Staff Member Will Dedicate to the Program

Identify which staff member will implement the plan. County or city officials will sometimes have someone who is already on staff implement the plan. More often, counties will create a new roadside vegetation manager position.

Ideally, the roadside manager will have wide-ranging knowledge and skills. The best candidates will have a solid background in operating heavy equipment, such as tractors, mowers, chainsaws, pickup trucks, trailers, skid loaders, tree planters, prescribed fire equipment, hand tools, seeders, and chemical spray equipment. They will also have good communication skills. Experience working with natural resources, vegetation, or both is an important bonus. Candidates must like a challenge and be willing to learn as they go. The county or city may hire the roadside manager before developing the IRVM plan and conducting the roadside vegetation inventory so the roadside manager can be involved in developing the plan. Conversely, the department hiring the roadside manager may prefer to write the plan first to articulate their vision for the program and develop local support for hiring a roadside manager to implement the plan. A generic position description (Appendix 2B) can be customized to fit your county’s situation.

Most roadside managers are responsible for at least 2,500 acres of roadside vegetation. They will be able to get more done if they have the assistance of a permanent or temporary technician and summer help. With proper funding, a roadside program has a sufficient workload to employ

- a full-time roadside manager/vegetation specialist,

- a full-time or nine-month roadside technician/assistant roadside manager; and

- two seasonal employees.

Results from the latest roadside manager salary survey can help when budgeting for staff salaries. The most recent survey results can be obtained from the Tallgrass Prairie Center roadside program manager. Potential funding sources in the county budget for roadside positions include the rural basic fund, secondary road fund, road clearing appropriation, and county conservation board budget. See Appendix 2B for a sample roadside manager job description.

The Full-Time Roadside Manager

The best way to achieve common roadside program goals is to hire a full-time roadside manager. As the person overseeing all roadside vegetation management duties, the roadside manager is focused and motivated to

- control weeds and brush in a timely, effective manner;

- save money by conducting more in-house operations;

- stay current with the latest products and technologies;

- establish and maintain healthy stands of native vegetation;

- install and maintain erosion control measures; and

- submit LRTF applications to bring in additional resources that address county needs.

The roadside manager takes ownership of managing the county’s roadsides with pride and accountability. When one person coordinates every aspect of the program, the result is better roadsides. Although cities may not have the resources to hire a full-time roadside manager, they need to designate in their integrated roadside vegetation management (IRVM) plans who will lead the effort to manage roadsides using the IRVM principles.

A Less Expensive Way to Get Started

A few Iowa counties have planted a lot of native vegetation in roadsides without a roadside manager. These counties do not have the same level of vegetation management as those with roadside managers, but they do have access to the LRTF. The following are examples of how this can be accomplished:

- The county engineer and conservation board director work together. The engineer applies for native seed from the Tallgrass Prairie Center’s Iowa Roadside Management Office at the University of Northern Iowa, or purchases seed for ditch cleanouts and roadside projects, and conservation personnel does the planting.

- The county identifies a current employee (e.g., the engineer or somebody working in the engineer’s department) who wants the county to use integrated roadside vegetation management. In addition to their regular duties, the employee applies for the native seed and works with road maintenance personnel to plant it.

- The county identifies a vegetation-savvy employee, most likely in the conservation department, and makes applying for LRTF grant funding and planting native vegetation in the roadside part of that employee’s job.

Hopefully, these and other similar nascent efforts by counties attempting to establish the use of IRVM principles act as catalysts to eventually hire full-time roadside managers. Maintaining healthy roadsides with native vegetation takes a sustained, focused effort. A county board of supervisors supporting the implementation of IRVM principles is necessary but not sufficient to make it happen—having an employee in a critical position who wants the program to succeed is crucial.

Steering Committee: Community Partners Who Can Help You With Referrals, Advertising, Implementation, and More

An IRVM steering committee (also known as an advisory committee) meets regularly to stay updated on the roadside program’s activities and challenges and provides guidance. The committee can also help spread the word within the community about the benefits of having a program and provide political support as needed.

A steering committee may be formed at any time but most often evolves from the committee formed during the initial effort to establish a program or is formed when a roadside manager is hired. A committee typically meets 2–4 times a year and consists of 5–10 members representing the private and public sectors. The committee may be comprised of some of the following members:

- member of the board of supervisors or city council

- Their support is critical, so the inclusion of at least one elected official is highly recommended.

- County/city engineer

- road superintendent/foreman

- weed commissioner (if this is a separate position from the roadside manager)

- member of the county conservation board

- key members of the original committee formed to establish a roadside program

- educator

- county soil and water conservation district representative

- federal Natural Resources Conservation Service employee

- residents interested in roadside management

- representative from a conservation organization such as Trees Forever or Pheasants Forever

- representative from a farming organization such as Farm Bureau, Soybean Association, Corn Growers Association, or someone involved in the agricultural industry

The county engineer, conservation board director, or initial IRVM committee members may recommend people to appoint but the county board of supervisors or city council has the authority to appoint members. Committee members often serve three-year staggered terms, which can initially be structured as follows:

- 3 members—1-year term

- 3 members—2-year term

- 4 members—3-year term

After this initial setup, when the terms are up, all subsequent terms would be for 3 years.

Committees elect chairpersons and secretaries, and meetings are subject to Chapters 21 and 22 of the Iowa Code concerning open meetings and public records.

Program Organization/Location

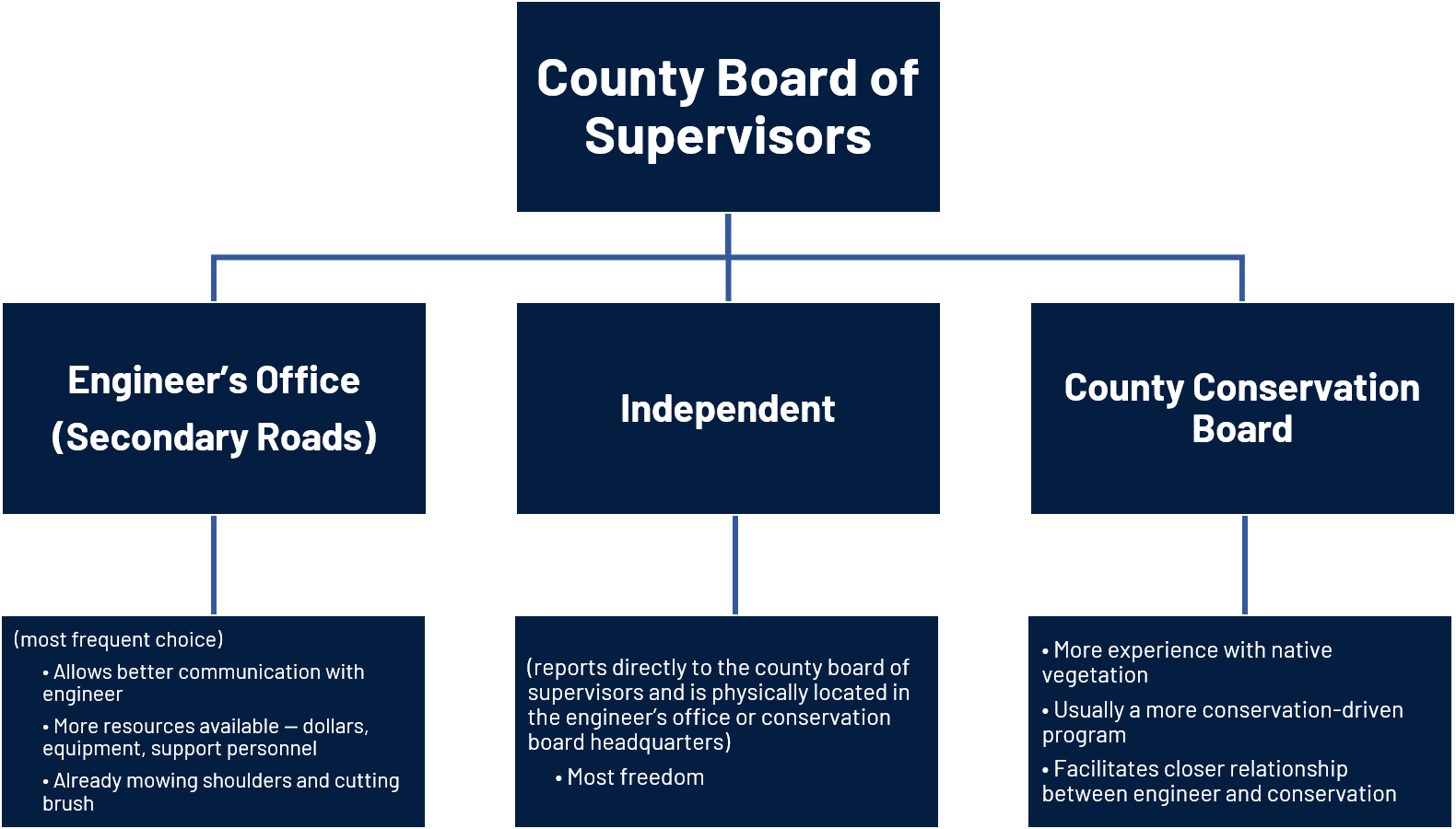

When deciding within which department to locate a county roadside program and who should supervise the roadside manager, keep in mind that greater independence allows for better planning and timely operations. Sometimes, a department may need to be restructured or reorganized to give roadside management personnel the autonomy to meet objectives. County programs can operate successfully within the engineer’s office, the county conservation board, or as an independent department. All three have advantages.

Generating Support for the Program

Members of the steering committee can generate goodwill for the program by communicating within their networks. Regular communication between the roadside manager and the committee members is important so that members know about the roadside manager’s projects and what information to relay.

Working on projects that visibly show progress in a relatively short amount of time, such as brush control or seedings with signage, can help garner support for a new program. The appropriate level and type of publicity for a new program can vary depending on the county or city’s goals and progress on specific projects.

Chapter 3: Communication includes many ideas for developing and maintaining both internal and public support for a roadside program.

How the Program Will Be Evaluated

Completing an IRVM plan and a county vegetation management survey can identify goals and objectives that serve as the basis for evaluating the program. Examples of ways counties have evaluated aspects of program success include:

- analyzing results of countywide roadside vegetation inventories;

- creating annual project reports documenting plant establishment for larger plantings (more than one acre) adjacent to hard-surfaced roads;

- evaluating the effectiveness of herbicides and other weed control measures in managing problem areas with a lot of invasive species; and

- examining the program's progress annually at one of the IRVM advisory committee’s regular meetings.

Budget

These expenses should be considered when anticipating the cost of a program:

- full-time roadside manager salary and overtime pay

- full-time technician salary and overtime pay

- temporary assistants’ salaries and overtime pay

- contract labor

- FICA payroll tax—county or city contribution

- Iowa Public Employees Retirement System (IPERS) city or county employer contribution

- employee health, life, dental, and long-term disability insurance

- herbicides

- stationery and other printing costs

- minor equipment and hand tools

- staff education and training

- operations and construction equipment

- fertilizer and seed

In the end, weed and brush control objectives are balanced against environmental concerns and limited county or city resources. With that in mind, determine an appropriate allocation of resources. Also, determine how much might be saved with better organization and efficiency.

Implementation

Implementation thompsbb

The following steps need to be taken during implementation, which is the period right before the actual date that the IRVM program officially begins and the months that follow.

Memoranda of Understanding

Partner organizations must sign any necessary memoranda of understanding.

Passing a County/City Resolution

The county board of supervisors or city council will need to pass a resolution establishing the program. Resolutions may also need to be passed or adopted regarding sections of the Iowa Code that pertain to IRVM programs, such as 314.22, and to accept LRTF grants. Work with other county or city staff to determine what resolutions are required.

Passing a Budget

Some counties and cities develop and submit the budget for the roadside program to be passed by the board of supervisors or city council, separate from other expenses, while others absorb the expenses in another department’s budget. In either case, it will need to be approved by the relevant county or city governing body.

Hire the Roadside Manager and Train the Staff

Provide the Tallgrass Prairie Center roadside program manager with the mailing address, email address, and phone number of the roadside manager leading the implementation of the IRVM program. The TPC roadside program manager will then provide the roadside manager with the following:

- The link to the online IRVM Technical Manual, with instructions on how to print sections should the roadside manager prefer a paper copy.

- Dates and locations for the next winter Association for Integrated Roadside Management (AFIRM) meeting, Roadside Conference, and Roadside Vegetation Programs 101 webinar.

- Information on the different responsibilities that the LRTF coordinator and TPC roadside program manager have so the roadside manager knows who to go to with questions.

- An inquiry to determine which field guides and brochures the roadside manager has, and providing any additional field guides or brochures that could be helpful.

- A request for a 3–5 sentence biography and photo to introduce the new roadside manager via the Iowa Roadside Management social media accounts and the Roader’s Digest email update.

- Information on how to reach out to nearby roadside managers who are willing to provide job shadowing for new roadside managers.

The TPC roadside program manager will then connect the roadside manager to the Iowa Roadside Management network by

- adding the new roadside manager’s contact information to the listing on the TPC website and internal email list consisting only of roadside manager email addresses; and

- adding the new roadside manager to the roadside management Google Group/email list and Roader’s Digest list, each of which is for those interested in roadside vegetation management.

Annual Operations

A list of annual tasks, duties, and projects can help the roadside manager understand their responsibilities throughout the year. Here is an example of a list of annual operations that appears in some IRVM plans. Some plans have a more detailed list that is organized by month.

- January–March: cut trees and brush, update seeding areas, attend the Association for Integrated Roadside Management winter meeting, attend the Iowa Weed Commissioner’s Association Annual Invasive Species Conference, submit the annual weed report to supervisors and the state commissioner, meet with the board of supervisors on roadside budget, and maintain equipment.

- March–April: conduct prescribed burning, apply for LRTF grants, check and replenish inventory, complete spring seeding as the weather allows, and hire and train seasonal employees.

- April–October: complete seeding, perform weed commissioner duties (supervise the control and destruction of all noxious weeds in the county), spray brush in ditches, mow first- and second-year seeded areas, manage seasonal employees, and attend the annual Roadside Conference.

- October–December: cut trees and brush, complete fall seeding, maintain equipment, write reports, check and replenish material inventory, and finalize the roadside budget.

Training and Continuing Education

Training and Continuing Education thompsbb

Job Shadowing a Neighboring Roadside Manager

After the roadside manager has begun working, the TPC roadside program manager will give the person an opportunity to job shadow an experienced roadside manager from a nearby county who is willing to help new roadside managers. This allows the new roadside manager to develop an early peer relationship and learn how another county approaches roadside management.

Chemical Safety/Handling

Controlled pesticide application is a useful part of the IRVM toolkit. Pesticide use in roadside rights-of-way is considered public pesticide application, which requires a state Commercial Pesticide Application license. To become licensed, the roadside manager must pass a 50-question, closed-book exam over the Core Manual - Iowa Commercial Pesticide Applicator Manual; pass a 35-question exam specific to right-of-way pesticide application; and pay a $15 fee for public applicators. Check here for Applicator Licensing and Certification testing dates from the Iowa Department of Agriculture and Land Stewardship.

Commercial Driver’s License

The Iowa DOT requires operators of vehicles that weigh at least 26,001 pounds to obtain a commercial driver’s license (CDL). Large pickups with trailers with a drill or spray equipment can top this weight. To obtain a CDL, applicants must complete applicable entry-level driver training from a registered training provider. Training providers charge an average of $4,000. For more information, see the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration Training Provider Registry.

Chainsaw Safety

There are several options for in-person chainsaw safety training:

- Have a representative from the company that manufactures the chainsaws you use come to your shop and train your employees. An advantage of this approach is that they can also look at your equipment and let you know if it needs any maintenance. A drawback is that some representatives may be less familiar with providing field demonstrations of safe brush removal techniques.

- Find an experienced county conservation board employee who periodically conducts chainsaw training.

- Find a nearby land management organization or nature center that periodically conducts chainsaw training.

- Attend chainsaw training at a community college with a land management program. For example, Hawkeye Community College regularly offers classroom-based chainsaw training with a representative from Stihl. Check with Hawkeye instructor Ryan Kurtz (ryan.kurtz@hawkeyecollege.edu) to find out when the next class is being offered.

- Receive training from a company that regularly conducts chainsaw training. These are more common in Wisconsin and Minnesota.

These are some useful online resources for chainsaw training:

- Forest Safety Instruction, LLC: Offering hands-on in-person safety training in the Midwest, including Iowa.

- Safe Training Online: Offering an OSHA-compliant online chainsaw training course.

- 360 Training OSHA Campus: Offering an OSHA-compliant online chainsaw training course.

Prescribed Burning

Controlled burns are a useful and cost-effective IRVM tool. Burning roadsides helps to control weeds, eliminate brush, and return nutrients to the soil. The Iowa Department of Natural Resources (DNR) forestry website lists relevant courses in prescribed burning. To become certified (known as “Red Card” certification) to conduct controlled burns, one must complete a field day (part of the S-130 firefighter training course) and a series of online courses. Field day options are usually listed on the Iowa DNR website in early spring.

Plant Identification

Identifying native and non-native plants is a vital skill for roadside managers. While recognizing noxious weeds may seem more important, it is equally important to recognize where native prairie plants are. Prairie remnants may be found on the sides of roads and train tracks. Remnant prairies are especially well-adapted to their environment, which makes them valuable sources for native seed.

Plant identification resources exist for every learning style. Commonly used resources are listed below.

Webinars

- Botany Beginners—Exploring Iowa’s Native Plants: This Tallgrass Prairie Center course includes six one-hour webinars teaching people the basics of plant identification using Newcomb’s Wildflower Guide as a resource, and three webinars produced in partnership with Practical Farmers of Iowa featuring hosts in a prairie pointing out common prairie plants.

- Botany Beginners—Grasses for the Masses: Seven one-hour webinars from the TPC about cool-season and warm-season grass identification.

- Botany Beginners—Managing Prairie Strips: A TPC course for those who manage prairie strips and other Conservation Reserve Program plantings within farmland..

- Golden Hills Resource Conservation and Development (RC&D): Plant identification webinar recordings, many of which are taught by botanist Dr. Tom Rosburg. Some of the webinars that might be especially useful to roadside managers include:

Books and Guides

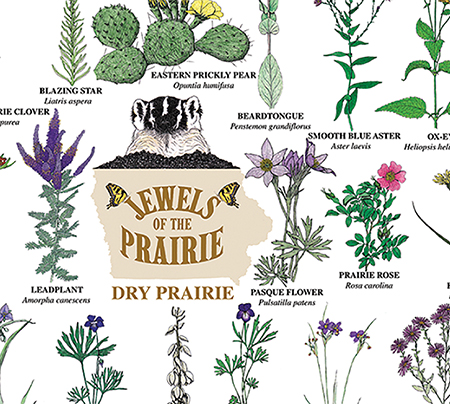

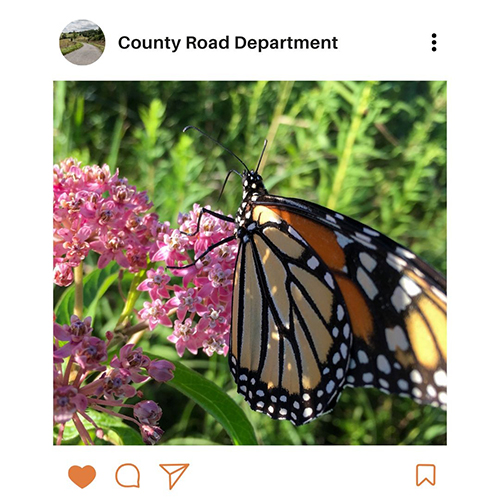

With training, roadside managers can develop a keen eye for native prairie plants, like butterfly milkweed (Asclepias tuberosa). Newcomb’s Wildflower Guide: This is the textbook used for the Botany Beginners courses. This guide contains both native and non-native wildflowers, shrubs, and vines. Its breadth (1,375 species) and easy-to-use key make it a valuable resource.

- Wildflowers of the Tallgrass Prairie: This is the textbook used for the Botany Beginners courses. This guide contains both native and non-native wildflowers, shrubs, and vines. Its breadth (1,375 species) and easy-to-use key make it a valuable resource.

- Wildflowers of the Tallgrass Prairie: The Upper Midwest: This guide contains high-quality images of 78 species, most of which are wildflowers. It is particularly useful for information on prairie remnants and ethnobotany. The guide is arranged in order of flowering time. It doesn’t include a key and has fewer species than the other books mentioned. The guide’s creators also produced complementary field guides for the wetlands and forests of the upper Midwest.

- Prairie Plants of the University of the Wisconsin–Madison Arboretum: : This is the most detailed guide on the list. It includes horsetails, ferns, rushes, sedges, grasses, shrubs, vines, weeds, and wildflowers and features both flower and fruit photos. Because the guide is arranged by plant family and doesn’t have a key, it is recommended for audiences who are already familiar with botany.

- Weeds of the Great Plains: This guide features weeds commonly found in Nebraska and neighboring states, including Iowa.

- Native Seed Production Manual: This TPC manual features basic information for native seed production of up to 100 species of the tallgrass prairie flora of the upper Midwest.

- The Prairie in Seed Identifying Seed-Bearing Prairie Plants in the Upper Midwest: This book includes plant identification, seed descriptions, seed harvesting and cleaning information, and more.

- The Tallgrass Prairie Center Guide to Seed and Seedling Identification in the Upper Midwest: This guide shows how to help identify and germinate 72 species of tallgrass wildflowers and grasses.

Websites

- USDA PLANTS Database: The Plant List of Attributes, Names, Taxonomy, and Symbols (PLANTS) provides standardized information about vascular and nonvascular plants and is useful for finding federal and state listings of weeds that are considered introduced, invasive, and noxious.

- Minnesota Wildflowers: This field-guide-style website has photos and information on Minnesota wild plants as well as guidance on how to search for them using multiple methods.

- Illinois Wildflowers: This website provides useful ecological information on the wild plants of Illinois.

- Iowa Weed Commissioners: This website includes weed identification brochures from nearby states and the Hawkeye Cooperative Weed Management website.

Plant ID Apps

Because plant ID apps aren’t 100% accurate, it is important to learn the basics of plant identification techniques using the resources above. That said, reputable plant ID apps can be used to provide roadside managers with a starting point when identifying plants. The apps also contain other information about species such as location, prevalence, etc. It is also good to be aware of the reputable apps to inform citizens who ask about them. Here are two that have been well-reviewed by amateur botanists.

Conferences and Field Days

Conferences Attended by Roadside Managers

The conferences listed below offer opportunities to network with other roadside maintenance professionals and participate in continuing education. Most roadside managers attend the winter Association for Integrated Roadside Management (AFIRM) meeting and the Iowa Roadside Management Annual Roadside Conference. Many also attend the weed commissioners conference, also known as the Iowa Invasive Species Conference. All three conferences include a lot of information directly related to roadside vegetation management and counties and cities are encouraged to budget for roadside managers to attend.

The other meetings listed are attended by fewer roadside managers, such as those who live near the meeting location. The TPC roadside program manager may be able to offer a limited number of scholarships covering the registration fee for roadside managers.

Winterfest—Iowa County Conservation System

- Approximate date: A three-day meeting typically held during the third or fourth week of January in Coralville.

- A variety of sessions led by academics and professionals working in conservation in Iowa and nearby states.

- Attended by a variety of county conservation staff and many college students on Wednesday for collegiate day.

- Includes an exhibition area with vendors and other organizations.

Winter Meeting—Association for Integrated Roadside Management (AFIRM)

- Approximate date: A one-day meeting held between late February to mid-March.

- Presentation and discussion topics are of interest to roadside managers.

Invasive Species Conference—Iowa Weed Commissioners’ Association

- Approximate date: A three-day meeting between late February to mid-March in the days immediately following the AFIRM meeting.

- A separate meeting for new weed commissioners is held in the late afternoon on the day of the AFIRM meeting.

- Presentations by researchers and practitioners, and an opportunity for continuing education in pesticide application.

- Attended by weed commissioners and conservation professionals whose role includes weed management.

- Includes an exhibition area with vendors and other organizations.

Iowa Prairie Conference

- Approximate date: Held every other year (typically in the years the North American Prairie Conference is not held) at a location in Iowa.

- Presentations about managing and restoring tallgrass prairie, with a focus on Iowa.

- Attended by natural resource professionals, researchers, and prairie enthusiasts.

North American Prairie Conference

- Approximate date: A four-day meeting held roughly every other summer at a location in the central United States.

- A focus on advances in managing and restoring tallgrass prairie ecosystems.

- Attended by researchers, students, and stewardship professionals.

- Includes an exhibition area with vendors and other organizations.

Roadside Conference—Iowa Roadside Management

The annual Iowa Roadside Conference includes presentations and opportunities to learn in the field. Approximate date: A three-day meeting in September or October.

- Includes an afternoon of field trips.

- Attended by roadside managers, Iowa Department of Transportation staff, and others interested in roadside management.

- Includes an exhibition area with vendors and other organizations.

Upper Midwest Invasive Species Conference

- Approximate date: A three-day meeting held every other year in mid-October to mid-November.

- One of the most comprehensive and largest invasive species conferences in the United States.

- Attended by a wide variety of researchers, natural resource professionals, and government agency staff.

- Includes an exhibition area with vendors and other organizations.

Conferences With a Roadside Management Table

The Iowa Roadside Management Office at the TPC has a table in the exhibition area at some of the events below to educate attendees about roadside vegetation management. The table may be staffed by the TPC roadside program manager or roadside managers, whose registration fees would be covered by the TPC. A small number of roadside managers may also attend some of these conferences on behalf of their county or city.

Statewide Supervisors Meeting

- Approximate date: A one-day meeting held in early February in Des Moines.

- Attended by members of county boards of supervisors.

- Includes an exhibition area with vendors and other organizations.

Iowa State Association of Counties Spring Conference

- Approximate date: Three-day conference held in March in Des Moines.

- Attended by all types of county employees.

- Includes an exhibition area with vendors and other organizations.

Iowa Statewide Association of Counties Fall Conference

- Approximate date: Three-day conference held in August in Des Moines.

- Attended by all types of county employees.

- Includes an exhibition area with vendors and other organizations.

Iowa County Conservation System Fall Conference

- Approximate date: Three-day conference held in mid-September at a location in Iowa.

- Attended by county conservation staff, especially conservation board directors and others in leadership positions.

- Includes an exhibition area with vendors and other organizations.

Iowa Streets and Roads Workshop and Conference

- Approximate date: One-day workshop and two-day conference held in September in Ames or Des Moines.

- Attended by secondary road and street maintenance supervisors and staff and others interested in road and street maintenance.

- Includes an exhibition area with vendors and other organizations.

County Engineers Conference

- Approximate date: Three-day conference held in mid-December in Des Moines.

- Attended by county engineers and other secondary road department staff.

- Includes an exhibition area with vendors and other organizations.

Field Days

Many conservation-oriented organizations and equipment dealers offer useful field days. The organizations listed below host virtual and in-person field events.

Practical Farmers of Iowa

- A series of free field days during the growing season on topics related to sustainable agriculture, including prairie seeding and burning.

- Attended by natural resource professionals and private landowners.

Prairie on Farms Program (Tallgrass Prairie Center)

- One or two field days (not held every year) on planting native vegetation in agricultural fields.

- Attended by farmers and natural resource professionals interested in prairie restoration.

Hawkeye Cooperative Weed Management Area Invasive Species Field Day

- An annual field day held in August at a location in eastern Iowa.

- Topics include managing invasive species and other land management topics.

- Attended by natural resource professionals and private landowners.

- Includes an exhibition area with vendors and other organizations.

Iowa Learning Farms

- A free webinar series on topics related to land management such as soil health, improved water quality, and pollinator conservation.

- All webinars are archived on its website.

Iowa Prairie Network Field Events

- Various prairie walks, seed harvesting, and prairie workshop events around the state.

- Attendees become more familiar with prairie plants and learn about Iowa’s natural landscape.

Email Lists and E-newsletters

Joining email lists and subscribing to email updates and e-newsletters is a good way to keep up with the latest news in roadside equipment, vegetation management, and roadside management in Iowa and beyond.

Roadside Management Email List

The TPC roadside program manager maintains a roadside management Google Group email list. Email the TPC roadside program manager to be added to the group. Group members can pose questions to the group to provide insight and search archives of previous questions. Members pose questions to the group to gain insight about others’ experiences with equipment, share job openings, and share time-dependent news that can’t wait for the monthly Roader’s Digest email update.

Roader’s Digest Email Update

The Roader’s Digest newsletter, deemed the “Newsletter of the Iowa Integrated Roadside Vegetation Management Program,” was established by the TPC roadside program as a paper newsletter from 1989 to 2009. In 2017 it was reinstated as a monthly email update. Subscribe and read previous email updates and archived issues.

Midwest Invasive Plant Network E-Newsletter

The MIPN e-newsletter contains invasive plant news from around the region. People can subscribe and read previous newsletters on the MIPN website.

Iowa Native Plant Society Discussion Group

The Iowa Native Plant Society maintains a discussion group available to anyone interested in native plants.

Professional Organizations

Belonging to one or more of the following organizations can be an avenue for making professional connections and keeping up with innovations in vegetation management:

Purchase Program Supplies and Equipment

Purchase Program Supplies and Equipment thompsbbTaking Advantage of the Living Roadway Trust Fund

Taking Advantage of the Living Roadway Trust Fund

Since 1990, counties have enjoyed support from the Iowa Department of Transportation’s Living Roadway Trust Fund (LRTF). Roadside managers submit applications each year to acquire resources for their programs. The LRTF does not fund salaries, tractors, or standard pick-up trucks; some heavy-duty trucks dedicated to IRVM activities may be funded. While eligibility for this funding requires only that a county have an IRVM plan on file with the LRTF, a county’s level of commitment to IRVM is a factor when grants are awarded. Having a full-time roadside manager demonstrates a strong commitment. Applications are due June 1 each year.

Since 1990, counties have enjoyed support from the Iowa Department of Transportation’s Living Roadway Trust Fund (LRTF). Roadside managers submit applications each year to acquire resources for their programs. The LRTF does not fund salaries, tractors, or standard pick-up trucks; some heavy-duty trucks dedicated to IRVM activities may be funded. While eligibility for this funding requires only that a county have an IRVM plan on file with the LRTF, a county’s level of commitment to IRVM is a factor when grants are awarded. Having a full-time roadside manager demonstrates a strong commitment. Applications are due June 1 each year.

Typical Equipment Needed for a Program

LRTF grants can be used to cover 80–100% of the cost of most of the items listed below. See the latest LRTF Funding Guidelines or contact the LRTF coordinator to verify if LRTF funds can be used for a particular purchase.

- heavy-duty pickup truck (¾ ton or large enough for a fire pumper unit)

- 60 horsepower tractor with dual rear axle

- flatbed truck for use as a herbicide spraying rig

- Many counties are using flatbed truck mounted spray units with chemical injection, spray heads, and GPS. LRTF will fund up to 80% of the cost.

- Sprayers are not a high priority for LRTF, so chances of approval are better if the city or county can cover more of the cost. The total cost can easily be $25,000.

- truck or trailer for hydroseeding

- broadcast seeder

- hydroseeder (minimum 800 gallons with mechanical agitation)

- six-foot native seed drill

- cultipacker

- boom mower

- chainsaws

- brush chipper

- GPS

- utility vehicle

- fire rigs and safety equipment

- straw mulch blowers

- harrows and drags

- trailers

- silt fence equipment

- equipment shed

- storage room

- herbicide storage equipment

- brush mowers

- broadcast seeder

Roadside Vegetation Inventories

The most effective roadside management starts with an accurate picture of the condition of roadsides in the county or city. A roadside vegetation inventory helps decision-makers set management priorities and provides baseline data for measuring program success.

Information collected in a roadside vegetation inventory includes herbaceous cover, tree and brush cover, weed concerns, bare areas, and areas with erosion and encroachment. The inventory development process typically involves a windshield survey, which means observing the roadside conditions while driving throughout the county or city. Windshield survey observations can be recorded every quarter mile or whatever interval is needed. Those conducting the inventory must be able to identify weeds, distinguish native prairie vegetation from non-native vegetation, and recognize areas of erosion and encroachment. If more than one individual is conducting the inventory in separate vehicles, training must be provided to ensure accurate, uniform data collection.

LRTF funds can be used to hire someone to do the inventory. The roadside manager and county engineer make the plan for the inventory process and train the person who does the inventory so the collected data will be accurate and useful. Allow six to eight weeks to complete the inventory. It is ideal to conduct the inventory in late summer or fall since this is the easiest time to identify stands of native vegetation.

If paid for by LRTF grant funding, rules stipulate that roadside inventories must be recorded on GPS devices. The LRTF provides free software for collecting and recording roadside inventory information. The LRTF also funds the purchase of GPS units, mapping software, and laptop computers.

Contact the Tallgrass Prairie Center roadside program manager or LRTF coordinator for information about contractors who conduct roadside inventories. Local college instructors and their students who are familiar with plant identification may also be potential resources for conducting inventories.

Identify Prairie Remnants

Every county in the state has a few roadsides containing small patches of native plants that descended from the original prairie. These prairie remnants may possess just a few species or they may be quite diverse. Either way, they provide a glimpse into the past and are valued as sources of genetic material and models for future prairie restoration. They merit protection.

Look for prairie remnants in places like an old railroad right-of-way that parallels the highway or land that may have been too rocky or wet to till. A thorough survey of roadsides in your jurisdiction is the best way to document the location of remnants and prevent their destruction. Generally, do not try to enhance a remnant by inter-seeding with native seed unless that seed comes from remnants in the immediate vicinity.

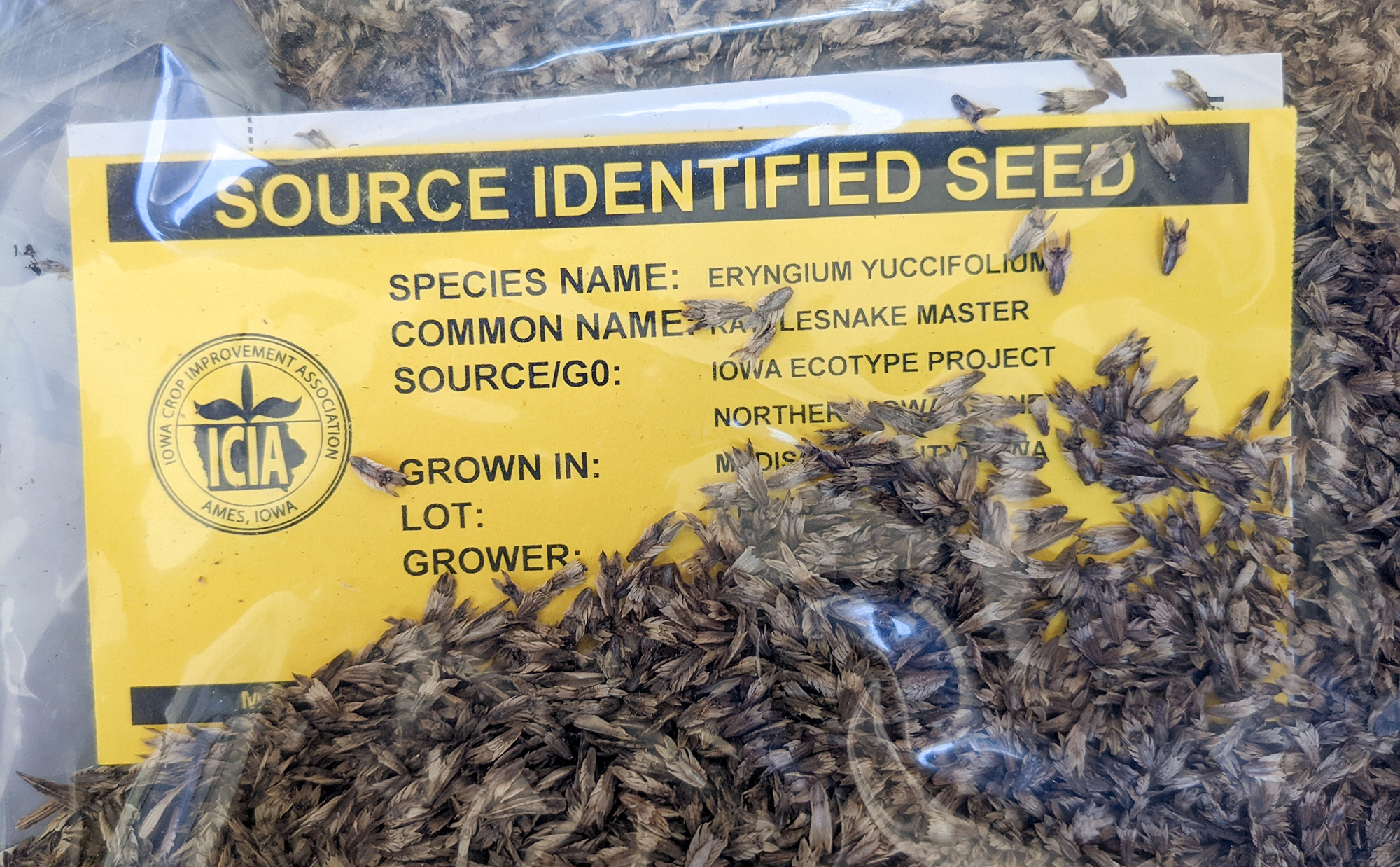

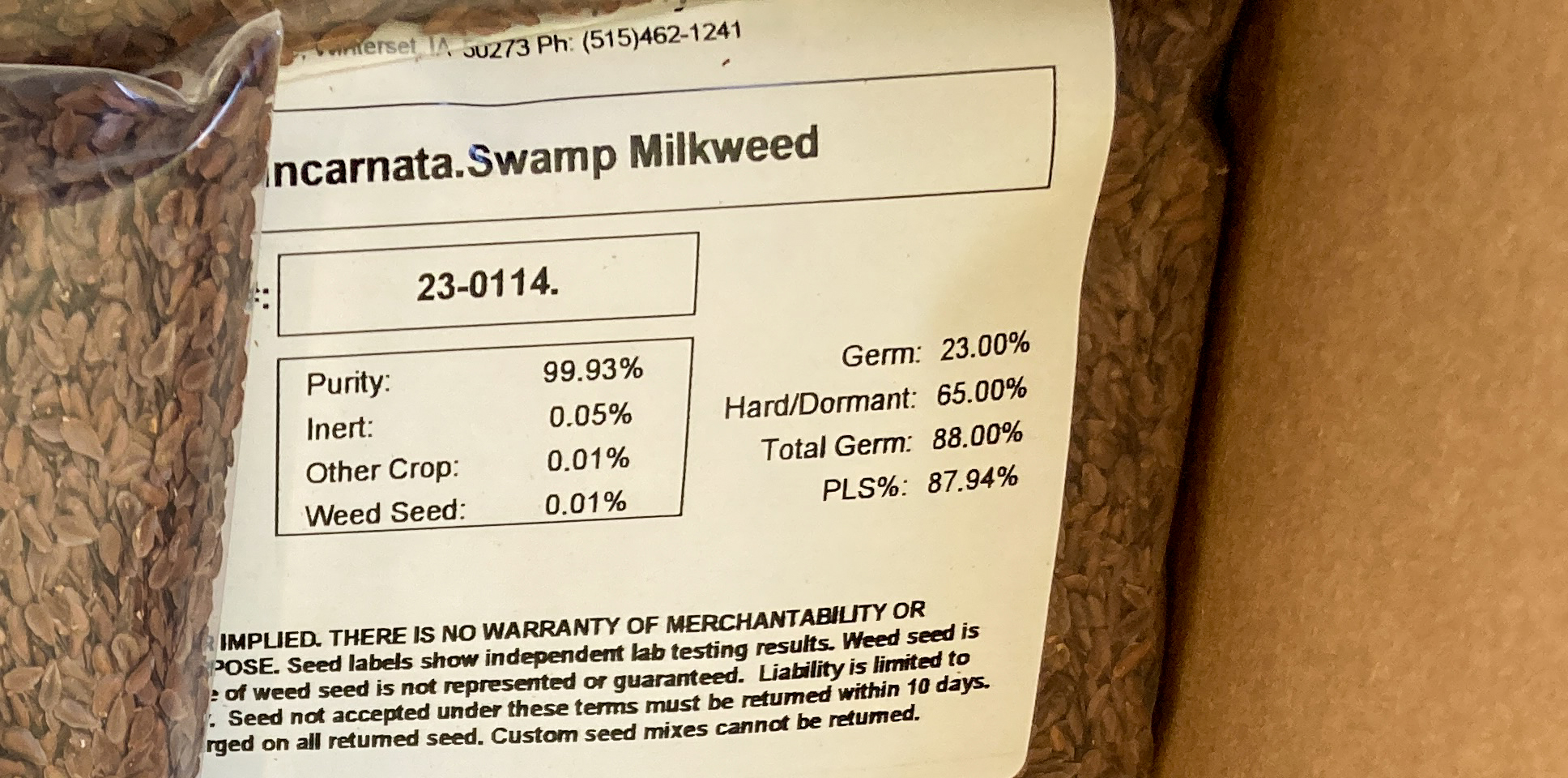

Native Seed From the Iowa Roadside Management Office

Since 1998, nearly all native seed planted in Iowa rights-of-way has been provided to counties and cities at no cost to them. This seed has often been paid for with Federal Highway Administration (FHWA) grant funding secured by the Iowa Roadside Management Office at the TPC. The FHWA program providing the grant funding has undergone several name changes over the years and is currently the Transportation Alternatives Set-Aside Program. Occasionally, this large seed purchase has been funded by the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation or the Living Roadway Trust Fund. These funds are approved annually.

No matter the funding source, counties and cities must file an approved IRVM plan with the LRTF and provide the labor and equipment to plant the seed. These native seed mixes have a value of $250–350 per acre and can only be used in road rights-of-way. For example, the seed cannot be used along trails that are outside of road rights-of-way.

Each September or October, the TPC roadside program manager emails eligible counties and cities to solicit seed requests for the subsequent year. Roadside managers will need to decide how many acres of seed they would like to receive and provide maps showing where seed will be drilled or planted using heavy equipment that may cause rutting of the soil greater than 6 inches. The Iowa DOT archaeologist will review this information to ensure no Indigenous burial sites will be impacted. Maps do not need to be provided for sites that will be hydroseeded or broadcast seeded since these methods cause only shallow soil disturbance that will not affect burial mounds.

The seed is typically distributed over a two-day period in April, May, or June at the shed south of the TPC in Cedar Falls. The seed must be planted by December 31 of the following year. Recipients must provide a seed report with maps every six months showing where the seed was planted.

A few counties have created their own seed production plots to supplement the seed they obtain from the Iowa Roadside Management Office. Establishing seed production plots requires a significant investment in terms of labor, land, equipment, and expertise for all stages of production. Counties also occasionally purchase seed from commercial sources to supplement what they receive from the Iowa Roadside Management Office.

Create Data Collection Tools and Processes Needed to Evaluate the Program

GIS mapping tools can be used to record data on roadside management activities such as brush cutting, spraying, and invasive species removal.

Chapter 3: Communication

Chapter 3: Communication thompsbb

Effective communication with county or city officials and the public is essential for building and maintaining support for an integrated roadside vegetation management (IRVM) program. Although roadside managers are busy with many responsibilities, regularly investing time in communication can pay dividends toward helping a program succeed.

Some roadside managers have been surprised at how they have been able to successfully use communication to gain support for their roadside programs from initially skeptical truck drivers, engineers, county supervisors, and others.

No matter who you are interacting with, best practices include

- being available and approachable to anyone seeking information or assistance;

- fostering trust by actively listening to stakeholders to understand their needs and consistently following through to accommodate their needs;

- promptly addressing complaints, concerns, and questions; and

- becoming the local expert on roadside management products and techniques and effectively explaining them to individuals unfamiliar with natural resources work.

Specific strategies for communicating with different stakeholders are presented below. As you read, keep in mind the amount of promotion and publicity needed to meet your goals can vary by county or city. A low-key approach might yield better results depending on local dynamics.

County Officials

County Officials thompsbb

County Board of Supervisors or City Council

Of all the relationships a roadside manager has, the relationship with the county board of supervisors (or city council for municipal roadside managers) is in many ways the most important. Supervisors approve IRVM program budgets, support grant applications, oversee individual projects, and more. Building and maintaining a close, collaborative relationship with the board lays the groundwork for a successful roadside program and sets the roadside manager up for success.

Members of the county board of supervisors can better understand roadside management programs if the roadside manager provides quarterly reports at board of supervisors meetings and invites supervisors on regular shop visits and tours. Engaging supervisors in discussions aligned with their interests, such as spraying weeds and brush mulching, helps build good relationships.

For example, aggressively spraying noxious weeds during the peak months of June and July and communicating about that work to the supervisors via an email update is one way to gain positive attention. Demonstrating progress in problem areas by sharing pictures of spraying and quantifying the work in acres treated shows the value of the work of the roadside manager. Showcasing projects and showing the supervisors that the work of the roadside manager is just as integral as any other facet of county road maintenance also helps garner support.

County Roads Department

Internal communication and outreach help foster good relationships, collaboration, and goodwill, including with colleagues in departments with which roadside managers work closest—county roads or city streets departments. A well-connected roads/streets team also makes for smoother workflows and decision-making processes.

Keeping engineers and secondary roads superintendents updated about planned actions is key to maintaining alignment with road projects. Involving secondary roads employees in brush control activities that transition from manual to more effective methods establishes good rapport with the roads department.

Offering training sessions to secondary roads employees on invasive plants, herbicide safety, and environmental concerns is beneficial for both departments.

Remember, because the roadside vegetation program staff consists of only 1–4 people, making connections with other staff is crucial. The benefits of being an integrated part of the county or city government are plentiful, and the consequences of allowing yourself to become siloed could put the program’s future at risk. These additional internal communication practices are worth considering:

- Be responsive. Fieldwork is the lifeblood of your job, but being out of the office frequently does not mean you should be hard to reach. Schedule time at your desk so you can reply to emails and return phone calls within 24 hours.

- Share updates from roadside vegetation management with the staff member responsible for county or city internal communications. They may include what you share in internal email updates, printed newsletters, etc.

- Offer to provide content about your program’s work for bulletin boards or display cases in county or city facilities.

- Introduce yourself to the county or city director of communications (or equivalent title) and express your interest in keeping county or city staff informed about the program.

- Volunteer for internal committees (e.g., social, hiring, strategic planning) to show your willingness to collaborate and make connections outside of the roads/streets team.

County Conservation

Leveraging collaboration between departments, such as the conservation board and public works staff, supports the transition toward an integrated approach in proposing ideas. Many of the tips for internal communication for the county roads department listed above can also apply to the county conservation department.

Reports About Iowa County Officials’ Perspectives on Roadside Vegetation Management

In 2016 and 2017, the Tallgrass Prairie Center (TPC) roadside program manager conducted research funded by the Living Roadway Trust Fund (LRTF) on perceptions of roadside vegetation management from roadside managers, county engineers, county conservation board directors, and chairs of the boards of supervisors. Personnel from all Iowa county officials were surveyed, regardless of whether they had a roadside program or not. The research was conducted with social scientists from the UNI Center for Social and Behavioral Research.

The survey results provide a sense of what stakeholders you will be working closely with think about topics such as mowing, soil erosion, cost savings, and the influence of roadside managers on the county’s overall approach toward use of native vegetation. These insights can be helpful to draw from when considering what topics to prioritize and emphasize when communicating internally. It is still important to talk to the stakeholders in your county or city to find out where they stand, as their opinions may vary from the general sentiment gathered from the survey. However, the survey results do provide helpful background information that can inform your strategic communications approach.

Survey questions for roadside managers and engineers primarily focused on how they manage roadside vegetation, such as:

- What have been your primary challenges in the greater use of native species?

- How often are your plantings typically mowed within one year of seeding?

- What weed prevention measures does your agency currently undertake in your county?

Survey questions for chairs of the board of supervisors and county conservation board directors included the following:

- What factored into your county’s decision to hire a roadside manager?

- How concerned are you about the possible effects of local prescribed burns?

- How much impact do each of the following items have on your county’s decisions about roadside vegetation management?

Reports summarizing results from all of these surveys can be found on the Tallgrass Prairie Center's "Survey Reports" page.

Understanding and Responding to Landowner Concerns

Understanding and Responding to Landowner Concerns thompsbb

Roadside managers enjoy a harmonious relationship with most landowners who live near roadsides they manage. However, some landowners will be critical of the IRVM approach. Some fear an increase in weed encroachment from the roadside, while others object to the appearance of native vegetation in the roadside. They may contact the roadside manager to voice their complaints. It is important to ask clarifying questions to understand their concerns before responding. The following scenarios and suggested clarifying questions are based on roadside manager feedback during a presentation about communication at the 2023 Roadside Conference.

Scenario 1

A landowner who moved from a city setting to a rural setting is unsatisfied with the unclean appearance of roadside plants and brush.

Suggested clarifying questions:

- What brought you from the city to the county?

- How would you define “unclean appearance?” What specifically is unappealing to you about the roadside?

- What would you like to know about how the roadsides are managed?

This information can be used to tailor a response to address the landowner’s specific concerns:

- Talk about the vegetation, explain what species are there, and help them make a connection between specific plants and the need for them to grow in a more natural manner, which may change the person’s mind about how the roadsides look.

- Enhancing roadsides is an investment in Iowa’s native habitat and wildlife that also keeps our roadsides safe.

Scenario 2

A landowner is concerned about roadside weeds encroaching on their property.

Suggested clarifying questions:

- Which weeds are causing you problems?

- What specific weed pressure (the visual percentage of how much volume weeds are occupying in a given agricultural area) issues do you have?

- What practices are you using to control weed pressure on your property?

This information can be used to tailor a response to address the landowner’s specific concerns:

- I would like to come take a look at the problem, assess the area, and come up with a solution for both you and the county.

- Native long-lived plants in roadsides suppress the kinds of weeds that tend to cause problems in crop fields.

- Explain the source of the weeds, whether it is from a neighboring property or from the roadside. If it is from the roadside, explain how you will remedy the situation.

Preventing Mowing and Spraying of Plantings

Sometimes, even after you have spent years maintaining a planting or remnant, the adjacent landowner may mow or intentionally spray it with herbicides, violating Iowa Codes 317.11 and 317.13. If this happens routinely with the same landowner, you may want to pursue monetary redress with the county or city attorney. However, if you are proactive with your communication strategy, you may be able to avoid having to take such action.

Some roadside managers have taken the preventative step of talking to landowners or placing doorknob hangers on their doors. In the form of a letter or brochure, roadside managers can explain why they are planting and maintaining native plants in the roadside, why the need for mowing and herbicide use is greatly reduced with such vegetation, and provide contact information. Subsequently, you could provide an annual one-page handout with text and photos updating landowners on progress made over the last year, any “by-the-numbers” facts (e.g., acres planted/maintained and cost-savings estimates), and any other news from the past year (e.g., new equipment purchase, new signage, grant funding secured). Make sure to include your name and a head-and-shoulders photo of yourself to make the communication more personal.

Establishing relationships and maintaining them is crucial to preventing adjacent landowners from mowing and spraying in the roadsides. This cannot happen without communication that shows respect for landowners and an understanding of the legitimate stake they have in how the roadsides are managed. Human nature indicates the landowners will treat you with reciprocal respect and deference to your area of expertise.

Public Outreach

Public Outreach thompsbb

Programs, Partnerships, and Events

Public Meetings and Community Events

Attending community events and public meetings can be an effective way to engage with the community. For example, some roadside managers have a booth at the county fair. Other events that may offer opportunities to set up an information booth include city festivals, Independence Day celebrations, harvest festivals, free outdoor concert series, farmers markets, and more.

In odd-numbered years, the Iowa Department of Natural Resources holds Resource Enhancement and Protection (REAP) regional assemblies around Iowa. These assemblies are public meetings where citizens can learn about REAP expenditures and provide feedback. Since 3% of REAP funding goes toward roadside vegetation management, roadside managers often attend the meetings in their regions to answer any questions about how those dollars are spent on managing local roadside vegetation.

In odd-numbered years, the Iowa Department of Natural Resources holds Resource Enhancement and Protection (REAP) regional assemblies around Iowa. These assemblies are public meetings where citizens can learn about REAP expenditures and provide feedback. Since 3% of REAP funding goes toward roadside vegetation management, roadside managers often attend the meetings in their regions to answer any questions about how those dollars are spent on managing local roadside vegetation.

County board of supervisor meetings and city council meetings also provide opportunities to convey to the public what you do and why you do it. Citizens who are active in local government attend in person. Others may watch the meetings on local government television channels, and many meetings are streamed live and/or archived online. Local reporters may be in attendance, providing an opportunity for additional media coverage. Maintaining a good relationship with supervisors and councilors as described above is a great way to get invited to meetings. But do not hesitate to reach out to staff who set the agendas for these meetings if you have not presented recently. See Chapter 2: Steps to Start a Roadside Vegetation Program for more on being a part of these meetings in the early stages of implementing an IRVM program.

Organizing Volunteer Events for Residents