Chapter 10: Managing for Extreme Weather

Chapter 10: Managing for Extreme Weather thompsbb

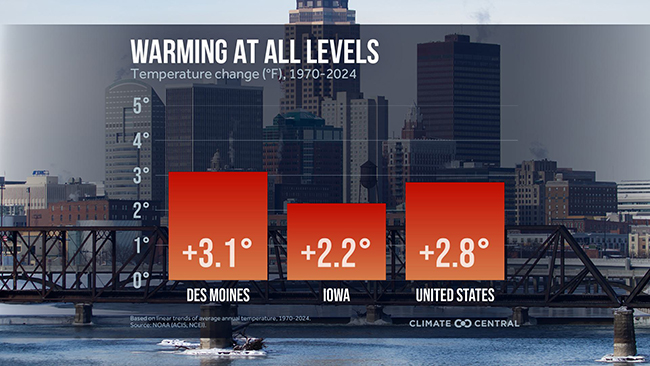

Des Moines’ and Iowa’s average annual temperatures have increased by 3.1 and 2.2 degrees, respectively, since 1970, following national trends (see Figure 10.1). Although this change might not seem like a lot, it is already having far-reaching consequences. Warmer air results in more evaporation of surface water from ponds, lakes, and rivers, releasing moisture into the atmosphere. Warm air can also hold more water vapor than cold air. For these reasons, rising temperatures are generally associated with increased precipitation. Overall, annual precipitation in Iowa increased by 4.1 inches between 1979 and 2021, with some parts of the state becoming wetter and other parts becoming drier.

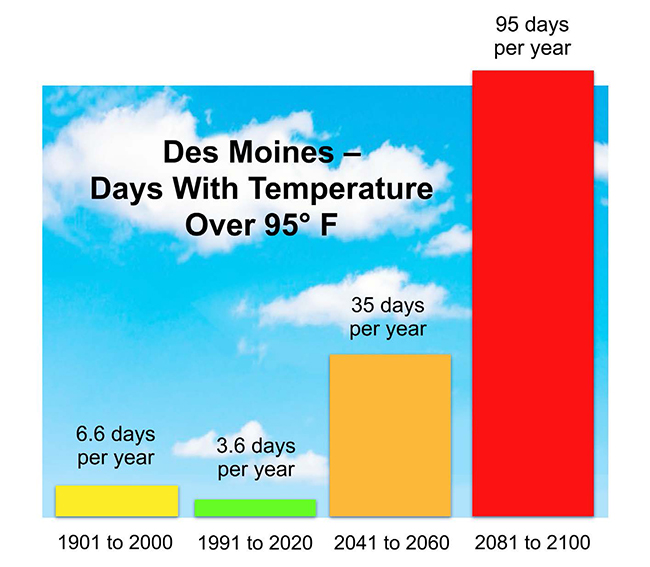

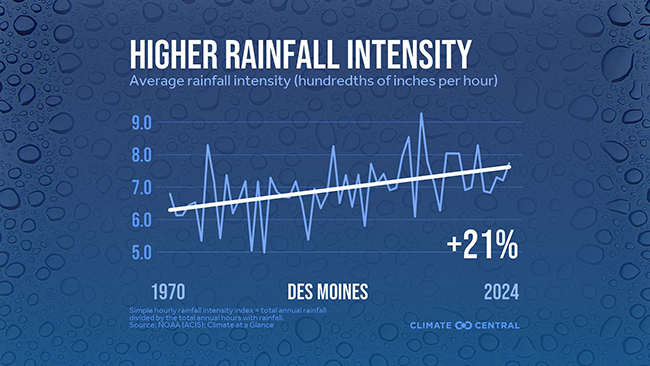

Iowa’s weather has also become variable and extreme in recent decades, including more days with extreme heat (see Figure 10.2) and higher rainfall intensity (see Figure 10.3). This trend is expected to continue in Iowa and worldwide.

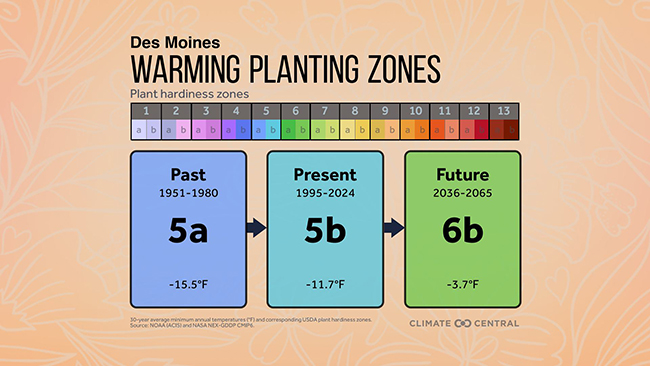

The outcomes of these continued changes in weather conditions, such as an increase in the duration of the growing season for native plants, flooding, erosion, dry conditions, and advantageous conditions for invasive species, can impact integrated roadside vegetation management (IRVM) practices. For example, plant hardiness zones, which are set by the United States Department of Agriculture to indicate which plants can survive the coldest expected temperatures felt during the year in a given place, are getting warmer (see Figure 10.4). Scientists are projecting the following additional direct and indirect weather-related impacts in Iowa in the coming years.

Direct Impacts

Direct Impacts thompsbbTemperature

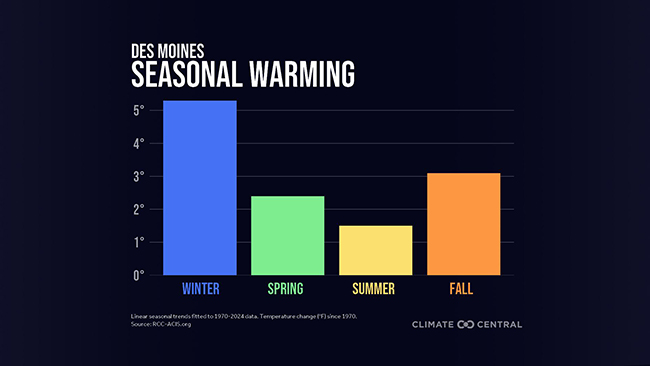

Figure 10.5. Seasonal warming in Des Moines in Des Moines from 1970–2024. (graphic by Climate Central, used with permission, climatecentral.org) All seasons are becoming warmer (see Figure 10.5), especially spring and winter (except for February).

- There are fewer cold nights.

Precipitation

- Heavy downpours with 2–3 inches of rain or more in one event are becoming more common.

- Spring and fall are becoming wetter on average, especially in April and October.

- Rapid-onset droughts, which are short in duration, are becoming more common in the summer with warm conditions and reduced precipitation in July and August.

- Most of the state experiences more than 40% of its annual precipitation on the 10 wettest days of the year.

Growing Season

- The duration of the growing season has increased by 8–12 days.

- Spring frosts are occurring earlier and fall frosts are occurring later than they used to.

Indirect Impacts

Indirect Impacts thompsbb

- Soil erosion, runoff, and flooding are becoming more common.

- Dry conditions lead to more dust from gravel roads landing on roadside vegetation, which decreases the effectiveness of herbicides.

- Drier summers mean less soil moisture available to plants.

- Nitrogen deposition in the soil is 2–6 times what it was in pre-industrial times, which gives invasive species a competitive advantage.

- Weeds and woody species, including eastern red cedar, are expected to expand because of warming temperatures.

- Cool-season invasive grasses like smooth brome are increasing, possibly because of increased rainfall early in the season.

- Increasing outdoor carbon dioxide levels help some invasives, such as poison ivy, thrive. Poison ivy also becomes more toxic because of rising carbon dioxide levels.

- Tick populations are rising.

- It is unclear if the types of species that are common in prairie vegetation will change in the coming years. Plantings and remnants with many plant species are more resilient, as the variety ensures the inclusion of plant species that are adapted to different conditions.

How Roadside Managers Can Adapt Their Management Strategies

How Roadside Managers Can Adapt Their Management Strategies thompsbb

- Consult with herbicide vendors to discuss mitigating the effects of reduced herbicide effectiveness due to dust. Mitigation strategies may vary depending on the brand of herbicide.

- Add as much plant diversity as you can afford when planting roadsides. A diverse seed mix, provided free of charge by the Tallgrass Prairie Center, includes species adapted to various moisture conditions, ranging from drought-tolerant to those that thrive in wet environments.

- Seed when weather conditions are favorable (see Chapter 5: Seeding).

- It is best to seed after it has rained, not before.

- If seeding in the spring, you may need to increase the seeding rate to compensate for seed that is dislodged during heavy spring rain events.

- If possible, do more dormant seeding, when the ground is not yet frozen but cold enough that seed will not germinate until the warmer spring months, to reduce the chances of extreme weather affecting your plantings.

- Conserve soil moisture by reducing mowing during drought conditions. If feasible, mowing vegetation at a height of 10 inches or more also helps conserve water.

Additional Extreme Weather Information

Additional Extreme Weather Information thompsbb